When I was volunteering at Housing Works Bookstore, one of the musicians who came to perform was a woman named Tift Merritt. I knew of her a little from my ex-boyfriend, and listened to a bunch of her music right around the time she played the show at Housing Works. Her most recent album at the time was “Another Country” and for a few weeks I kept listening to its title song, with its simple, sweet plaintive refrain:

I thought these things would come to me

Love is another country, and I want to go –

I want to go too. I want to go with you.I want to go too. I want to go with you.

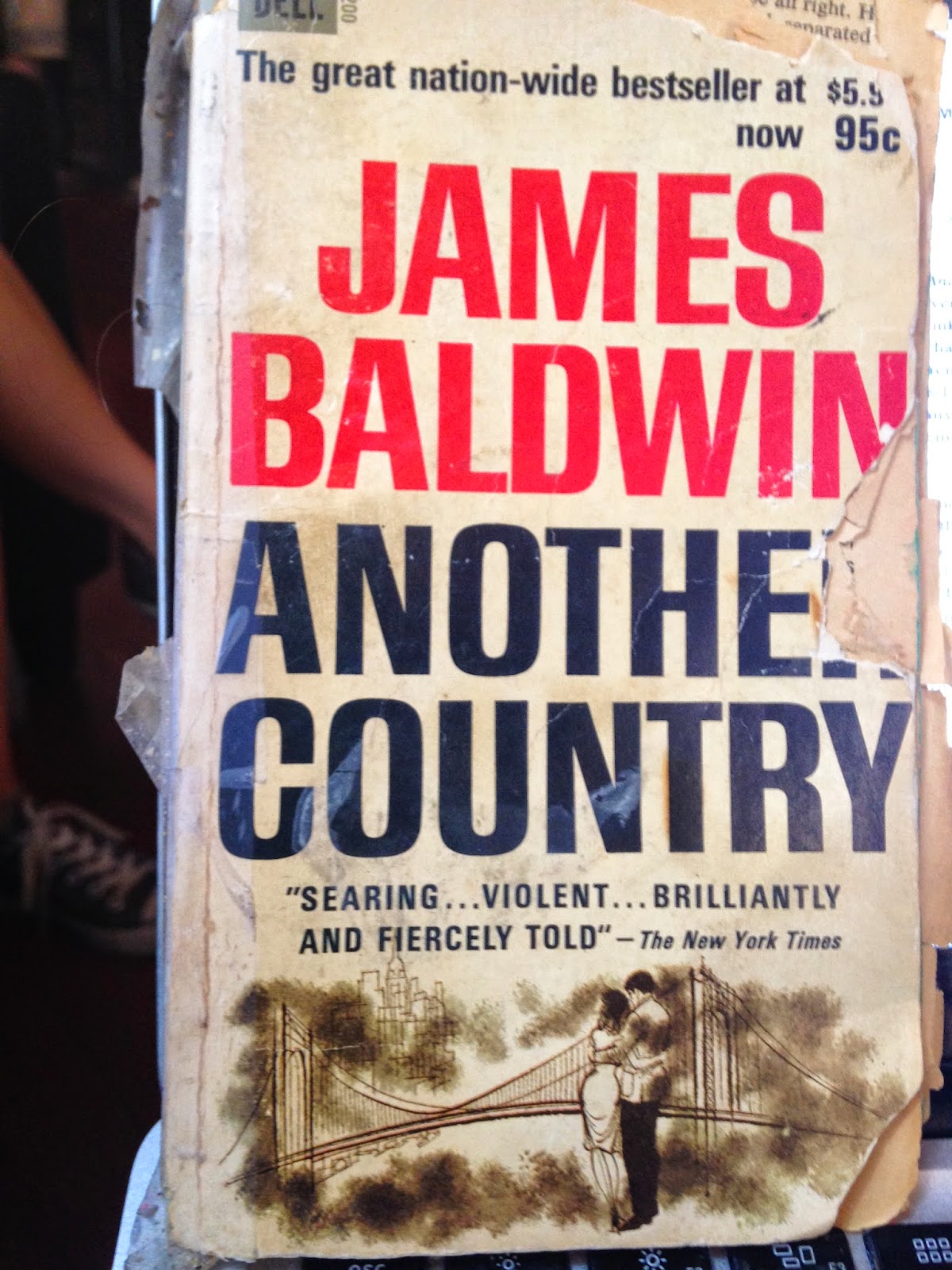

So I decided to start remedying this by reading Another Country, Baldwin’s 1963 novel, the next work of fiction after Giovanni’s Room. I had a falling-apart paperback of this one also. I think I inherited from my grandmother’s library. I like to imagine her reading it as a forty-something faculty wife, when she looked like a happier Mona Sterling in her impeccable blouses and tailored skirts. Like a lot of the feminist books from later in the 60s I’ve been researching, the books packaging combines commercial hype and political import in a way that’s almost impossible to imagine today. On the back, Granville Hicks intones “The book itself is, and is meant to be, an act of violence.” (It isn’t, of course, and that Hicks thinks so – and thinks this is a selling point – would be another post in of itself).

As this cover illustration suggests, Another Country is first and foremost a New York novel. Like so many writers, Baldwin left the place he was from to write about it. The middle section takes place in Paris, but he didn’t write it there either. Below the final scene, charting the arrival in New York of a character’s French lover to New York and these “people from heaven,” there’s a dateline reading “Istanbul, December 10, 1961.” I happened to finish Another Country around the same time I read this New Yorker essay about Erich Auerbach, who famously completed Mimesis, a founding work of my original discipline of Comparative Literature, in Istanbul. Auerbach was fleeing the Nazis; Baldwin was fleeing racism, fame, and all the things that make it as difficult to write in New York as it is to write about New York. He came at the invitation of his friend Engin Cezzar, and the photographer Sedat Pakay took amazing photos of him there.

One of the many fascinating things about Another Country is the lost New York it gives us. Baldwin’s group of writers, artists and drifting souls (there’s no one central character, and a lot of fascinating misdirection around this), hang out mostly in the Village. Some characters like to go to Harlem for “tomcatting,” as they put it. One white woman has run away from the south, fleeing an abusive husband who has taken custody of her children. Brooklyn is the place of childhood everyone runs away from. And much is familiar: everyone in the group is suspicious of the writer whose novel is having some commercial success, and everyone drinks too much. They hang out at Smalls.

Baldwin’s characters are exiles of a different sort than Auerbach or Baldwin. They flee their isolation and the repression of their families. They run headlong against the cruelties of the culture they come from, unable to treat each other better than they have been treated, but blessed or cursed with enough self-knowledge that compels them to keep trying. Their other country is their own, and Baldwin takes pains to render his own New York strange as well, as when we are given the city through the eyes of another exile, the actor Eric upon his return to France:

So superbly was [New York] in the present that it seemed to have nothing to do with the passage of time: time might have dismissed it as thoroughly as it had dismissed Carthage and Pompeii. It seemed to have no sense whatever of the exigencies of human life; it was so familiar and so public that it became, at last, the most despairingly private of cities . . . The girls along Fifth Avenue wore their bright clothes like semaphores, trying helplessly to bring to the male attention the news of their mysterious trouble. The men could not read this message. They strode purposefully along, wearing little anonymous hats, or bareheaded, with youthfully parted hair, or crew cuts, accoutered with attaché cases, rushing, on the evidence, to the smoking cars of the trains. In this haven, they opened up their newspapers and caught up on the day’s bad news. Or they were to be found, as five o’clock fell, in discreetly dim, anonymously appointed bars, uneasy, in brittle, uneasy, female company, pouring down joyless martinis.

Geography and sex and ritual: Baldwin stirs them so that it is impossible to maintain our convenient fiction about which part of ourselves comes from an “external” society and which from “internal” desires. This, I think, is why their jealousies, adulteries, and drunken rages seem large rather than petty. Sexual and racial repression is part of it, but I don’t think this is just a case of “when nothing is permitted, everything matters.” Hipster alienation and rebellion have become such a cliche it is startling to view characters for whom estrangement from their families and communities are a real, definitive rupture that could easily leave them destitute and isolated. At the same time, in New York they have the means to peruse their desires and realize what this does and does not do. It is one thing to parse out all we know or think we know about desire, repression and “the other,” when we see Vivaldo, an Italian-American “unpublished novelist” from Brooklyn peruse Ida, an African-American singer whose brother is probably the person Vivaldo is actually in love with. It is another thing to try, as Baldwin does, to imagine what both such people think and feel as they undertake this doomed but sincere bond. Here is Vivaldo watching Ida perform:

She was not a singer yet. And if she were to be judged soley on the basis of her voice, low, rough-textured, of no very great range, she never would be. Yet, she had something which made Eric look up and caused the room to fall silent; and Vivaldo stared at Ida as though he had never seen her before. What she lacked in vocal power and, at he moment, in skill, she compensated for by a quality so mysteriously and implacably egocentric that no one has ever been able to name it. The quality involves a sense of the self so profound and so powerful that it does to so much leap barriers as reduce them to atoms – while still eating them standing, nightly, where they were; and this awful sense is private, unknowable, not to be articulated, having, literally, to do with something else; it transforms and lays waste and gives life, and kills.

Thanks for this post, Laura! I'm a Baldwin-lover too, and I questioned the NYT story stating that Baldwin is being taught less in classrooms than he once was. It seems to me that Baldwin's Go Tell It on the Mountain may be taught less, but as Gay & Lesbian studies classes/programs have grown, Giovanni's Room or Another Country may be being taught more. And I think it's only recently that the publishing world acknowledges that POC can write about subjects (sexuality, science, business) other than race, and also, that white people are capable of writing about race.

Thanks! I wondered about that article too – maybe more true of high schools, in part because of testing (hence doing Sonny's Blues rather than a full book)? One of our LaGuardia colleagues just taught Another Country in gay/lesbian lit, and I'm going to do Go Tell it on the Mountain in 102 next winter. Hoping to work through some more gaps in what of his I've read soon.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.