When I was a kid I sometimes watched a show my dad liked called The Prisoner. It takes place on an island that gets a new ruler each episode, referred to as “number 2.” (You never find out who #1 is). Every episode the main character tried to escape the island and every episode he was brought back in a big clear bubble. In one episode, he made a boat that he disguised by taking it apart and putting it in art exhibit. He calls it “escape.” But what does it mean, a guard at the exhibit asks. It means whatever you want it to mean.

By Prof. T.

10 Great Books for Small Children, and What Makes Them Great

Nearly four years into this whole parenting thing, I have no great unified theory of parenting. I do have a theory about kids books, though. To me, there is no failed literary experiment or abstruse academic text so baffling as the children’s book written by someone who has apparently never read a book to a child. What’s interesting about these books is that if you describe them they often don’t sound so terrible, but trying to read them you have no choice but to change the words. The words don’t track, don’t fit the story, don’t fit the pictures. They’re invariably overwritten. I’ve never gone along with the whole kill-all-the-adjectives and adverbs thing, but it’s really true for picture books.

With this lovely Ben Lerner LRB piece in mind, about (among other things) how the existence of Really Bad Poetry can help us think about what good poetry is, I’ve been thinking about what these baffling books can tell us about what makes a great book for little kids. Here’s what I’ve come up with: a good picture book aspires to the condition of poetry. That is, it has to use some combination of the things that make poetry poetry: condensed and/or heightened language, attention to rhythm, rhyme or sound, repetition and variation, attention to how words are presented on the page. With picture books of course that means not only arrangement and typeface but how the pictures interact with the words. A bad or mediocre picture book often reads like the author had an idea, often seemingly based on something they liked as a kid, wrote it up in excruciating detail, then had someone draw some related pictures.

So here are ten picture books that have given me a lot of pleasure, and that my son also loves. (There are lots of so-so books that kids love that can drive parents crazy with enough repetition; there are lots of crappy ones that can’t hold a kid’s attention; the really good ones appeal to both.)

Some of these are pretty well known but I tried to included some less known ones, or somewhat lesser known ones by well known authors.

In no particular order:

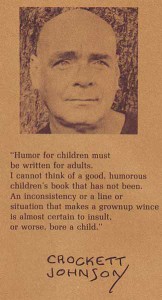

1) Harold’s Fairy Tale, by Crockett Johnson (1956).

One of many follow-ups to the also wonderful Harold and the Purple Crayon. An epitome of words and pictures synthesis, as Harold draws the world as the words create it. Lore Segal, best writing teacher I ever had once told a story about sharing a hallway with Malamud who told her he was writing a story about a runner, which was very hard, because he had to make the world he ran through. That’s what these books are about. For me, Fairy Tale is even better than the original because its story, about how creating an imaginary king and imaginary gardens, is so wittingly subversive. So imagine my delight to find out Crockett Johnson (born David Johnson Leisk) was a big old commie who wrote cartoons for the New Masses. The books are funny too. (An interesting thing I’ve learned is that a lot of children’s book authors and illustrators had really fascinating lives.)

Today in Feminist History: Alice Paul and The Night of Terror

On November 15, 1917, Alice Paul, the thirty-two year old founder of the National Woman’s Party, had begun serving a seven month prison sentence, purportedly for blocking traffic but in reality because of the series of provocative protests targeting President Wilson. NWP called Wilson “Kaiser Wilson,” targeted a meeting between Wilson and the new Russian government, and staged the first ongoing picket of the White House and burned copies of his speeches, a particularly bold action during a time of war and repression of dissent.

Today in Feminist History: On Lee Miller

Word came this week that Kate Winslet will star in a movie about Lee Miller. It’s certainly a life that begs for cinematic treatment: Miller was a young model, a muse and collaborator to Picasso, Man Ray and Jean Cocteau who became one of the most important photographers and war photographers of the century. Her work ranged from abstract treatments of the Egyptian landscape to the war photographs she is most known for. A while ago, I published a poem inspired by a photograph of her in Hitler’s bathtub at his house in Munich, where Miller and collaborator David Scherman arrived a few days ahead of the American troops. She and Sherman came to the home from Dachau, where they were among the first photographers to arrive. There’s so much about that picture I love: the boots and dirty bathmat seem more beautifully irreverent and darkly hopeful than Mel Brooks’ dancing Nazis could ever hope to be. Given Winslet’s somewhat well-known penchant for movies that ask for tasteful or meaningful artistic dis-robing, I can’t help but wonder if this photograph will play a role in the movie.

I got interested in Miller after reading a chapter about her in Francine Prose’s The Lives of the Muses. It’s a collection of short biographical essays, probably my favorite genre, and not only because I usually get overwhelmed by shopping-list level of detail in full-length biographies. It’s also the perfect genre for the women Prose writes about, all of whom struggled in one way or another with their own creative ambitions, the politics of the artistic circles in which they travelled, and the not insignificant calculations behind whether, how, and for how long, to sleep with the artist in question. (Prose goes on a bit defensively in her introduction about defending her subject from the charge that the muse is anti- or at least non-feminist, but the stories themselves are universally fascinating looks at sexual politics, although I did wish she’d mixed it up a bit with chapters on Neal Cassidy, Alice Toklas or Natalie Barney, to name a few.)

In the bathtub picture, Miller plays both roles: she didn’t take the picture, obviously, but she had the idea for it, and you don’t have to have read Laura Mulvey to realize there are worlds going on in her look.

The war divided Miller’s life. Her life after the war was marked by heavy drinking and depression, likely related to her war experiences. She was also a legendary hostess whose farm was a legendary salon for artists and others. Her only child was born in 1947, when she was 40. Throughout the 40s and 50s, MI-5 spied on her for communist tendencies. There being no evidence of espinoge, her communism is described as “more of a mental outlook.” Her boss at Vogue told the spooks: “She is eccentric and indulges in queer food and queer clothes.”

The film is based on a book by Miller’s son, who was born after her artistic working life had ended and knew little of it until after she passed away. Given the well-known dangers of the bio-pic, I dread watching Winslet play drunk in bad aging makeup, or some movie of the week tripe about the conflict between work and family. If I were making it, (call me!) I would be tempted to have two unconnected scenes: one around the making of the one film she was in: Jean Cocteau’s “The Blood of Poet,” in which she played a statue, and one on the day in that apartment: show them coming to the idea, show her and Sherman talking: what more “tensions” do we need than that distance?

Today in Feminist History: Anniversary of an Anniversary

On August 26th, 1920, the 19th amendment granting women’s suffrage went into effect. It was the result of years of ceaseless toil:

“To get the word “male” out of the constitution cost the women of this country 52 years of pauseless campaign. During that time they were forced to conduct 56 campaigns of referenda to male voters, 480 campaigns to get legislatures to submit suffrage amendments to voters, 47 campaigns to get state constitutional conventions to write women into state constitutions, 277 campaigns to get state party conventions to include women suffrage planks, 30 campaigns to get presidential party conventions to adopt woman suffrage planks in party platforms and 19 campaigns with 19 successive Congresses.” (Carrie Chapman Catt and Nettie Rogers Shuler, Women Suffrage and Politics, quoted in Shulamith Firestone, “The Women’s Rights Movement in the U.S.A.: New View, Notes from the First Year) Read more

Today in Feminist History: Shirley Chisholm on the ERA

Forty-five years ago today, Shirley Chisholm speaks on behalf of the Congressional passage of the Equal Rights Amendment:

“This is what it comes down to: artificial distinctions between persons must be wiped out of the law. Legal discrimination between the sexes is, in almost every instance, founded on outmoded views of society and the pre-scientific beliefs about psychology and physiology. It is time to sweep away these relics of the past and set further generations free of them.” Read more

The George Washington Bridge: “Inside Llewyn Davis,” James Baldwin, and Portraits of Grief

I looked forward to watching Inside Llewyn Davis for a long time before it came out. I grew up on folk music and some of these songs will probably be the last thing I remember when I’ve forgotten my own name. I wasn’t disappointed, but a lot of people were. Critics and friends alike – and my folk-loving parents – all focused on the how “unlikeable” Davis was – like David Edelstein, they found him/the movie “sour” or “snotty.” I was intrigued by this reaction. As anyone whose read a single think piece about the “Golden Age of Television” knows, we’re living in the age of anti-heroes: the more anti the better. So what had Llewyn done that soured the deal when unrepentant murderers, meth dealers, and racists were compellingly “complex”?

The brilliant Eileen Jones writes persuasively in her piece at Jacobin that viewer’s contempt has to do with the American valorization of success – the film doesn’t give its hero a narrative of upward mobility, of movement towards success, and we’re not open to stories of failure, so much so that “If Inside Llewyn Davis weren’t so funny, none of us could stand it.”

I think she’s undeniably right about all of that. But after watching the movie again recently, I was struck by the extent to which it is also a movie about grief. It strikes me that Davis’ problem isn’t that he’s not talented or successful enough, it’s that his friend and former singing partner died in a terrible way, and he doesn’t pretend not to be wrecked by that.

I think I missed this the first time because Davis doesn’t talk a lot about his grief – and that’s the point. Like unrequited love, grief in a happiness-obessed and death-denying culture is the love that dare not speak its name. This time, when, midway through the film, we learn through a conversation with John Goodman’s unsympathetic jazz musician that his friend jumped off the George Washington Bridge, I thought of another portrait of New York Bohemia from around the same time, James Baldwin’s Another Country. Here we have another suicide by another young musician from the same bridge. Unlike in Inside, Baldwin takes us right to the scene:

Read more

Today in Feminist History: Marlene Sanders, 1931-2015

For my research reading Bonnie Dow’s excellent “Watching Women’s Liberation 1970.” One point she convincingly makes is that coverage of the movement was not as uniformly hostile as we might expect. Part of this was due to women like Marlene Sanders, who died this week, and, among other things, produced a substantive piece on the Ladies Home Journal strike of 1970. As Dow explains, activist Susan Brownmiller cultivated this sympathetic coverage by leaking word of the sit-in to Sanders in advance, assuring she would be the one on the scene. There are a lot of great stories of these little collaborations at the time – my favorite being another one Dow describes, when a secretary at Playboy leaked to feminist activists a memo Hugh Hefner had written asking for “a devastating piece that takes the militant feminists apart.” Dow devotes a chapter to the documentary she produced for ABC about the movement and how she navigated her sympathy for the movement with her position at the network and her views about the role of journalists. Those of us on the left are rightly suspicious of the idea that getting more people of X group on the inside is a solution to social injustice, but in this case it did really make a difference.

Some Stupid Test

Over the course of my sabbatical, I’m hoping to write a range of personal reflections on teaching. It’s a hard topic to talk about. A lot of the formal scholarship is notoriously bad, which makes a lot of teachers hesitant to read about it, which is a shame. One aspect of teaching I think about a lot is how our own histories as students shape the way we teach and, especially, how we relate to our students. One of the reasons I think faculty diversity is important, despite being an inadequate method of addressing institutional racism and sexism, is that people tend to mentor students who remind them of themselves. And one thing most, though not all academics have in common is the experience of being told they were “smart,” of doing well on tests, and, crucially, getting the message that intelligence wasn’t just a tool, it was an identity. At its best, this identity can help people develop and take pride in their capacities and curiosities and resist our anti-intellectual culture; at its worst, it can foster smug superiority, the belief that if one is brilliant, everything one does must be brilliant too. When too many people who’ve been told this their whole lives are put in the same place, you get this.

Read more

Misty Copeland

In another life, like countless girls, I spent countless hours dreaming about ballet. I subscribed to Dance Magazine, I sewed ribbons into shoes, and I watched a VHS tape we had of the Kirov’s production of Swan Lake dozens of times. I read Gelsey Kirkland’s memoir on the beach and cried.I wasn’t very good. But I kept practicing, and I cared about it deeply. I think it was invaluable for my young physical self growing up in a very anti-sports family, and to my love of the arts. One summer I went to a ballet camp and there was this imposing teacher everyone was scared of. But one day he broke character and had us huddle around and talked about the worthiness of our calling. He did a probably offensive but very funny imitation of a ditzy high school girl and asked if those girls made fun of us for dancing. He told us, just remember, what do they do? Nothing. What do you do? You dance. He made it sound sacred.

When I got to college (a woman’s college I’d picked in part because they had a dance program), I realized quickly a lot of budding feminists saw ballet as a very bad thing. It fetishized little girls, it gave them eating disorders, it was aristocratic, elitist, etc. etc. I could see where they were coming from, but my heart wasn’t in it. Later in graduate school when I met the Marxist who would become my advisor, I sheepishly mentioned I had been a dancer once, in another life. “Ah, she said. That’s so wonderful! The physical discipline!” That’s probably the moment I knew she would be an important figure to me.