I looked forward to watching Inside Llewyn Davis for a long time before it came out. I grew up on folk music and some of these songs will probably be the last thing I remember when I’ve forgotten my own name. I wasn’t disappointed, but a lot of people were. Critics and friends alike – and my folk-loving parents – all focused on the how “unlikeable” Davis was – like David Edelstein, they found him/the movie “sour” or “snotty.” I was intrigued by this reaction. As anyone whose read a single think piece about the “Golden Age of Television” knows, we’re living in the age of anti-heroes: the more anti the better. So what had Llewyn done that soured the deal when unrepentant murderers, meth dealers, and racists were compellingly “complex”?

The brilliant Eileen Jones writes persuasively in her piece at Jacobin that viewer’s contempt has to do with the American valorization of success – the film doesn’t give its hero a narrative of upward mobility, of movement towards success, and we’re not open to stories of failure, so much so that “If Inside Llewyn Davis weren’t so funny, none of us could stand it.”

I think she’s undeniably right about all of that. But after watching the movie again recently, I was struck by the extent to which it is also a movie about grief. It strikes me that Davis’ problem isn’t that he’s not talented or successful enough, it’s that his friend and former singing partner died in a terrible way, and he doesn’t pretend not to be wrecked by that.

I think I missed this the first time because Davis doesn’t talk a lot about his grief – and that’s the point. Like unrequited love, grief in a happiness-obessed and death-denying culture is the love that dare not speak its name. This time, when, midway through the film, we learn through a conversation with John Goodman’s unsympathetic jazz musician that his friend jumped off the George Washington Bridge, I thought of another portrait of New York Bohemia from around the same time, James Baldwin’s Another Country. Here we have another suicide by another young musician from the same bridge. Unlike in Inside, Baldwin takes us right to the scene:

Read more

From music

White Guys Drive Like This, or, How to Write about Music

A remember, years ago, sometime in the early 90s, hearing a joint interview on NPR with the poets Donald Hall and Jane Kenyon. I’m going from memory here, as is permitted in a blog post, no? They were married; Kenyon died not long after I must have heard the interview, and Hall’s poems about this are probably what most people know about him, if anything. Anyways, it was a typical NPR-kind of interview, in that on some level the interviewer knew that most people listening didn’t really care much about poetry, but might be interested in hearing a married couple banter about their creative work. So I remember a bunch of questions about when they would give their work to each other and such. At one point one of them mentioned that they had both recently written poems about the first Gulf War (of course just called the Gulf War then), and that they had shared them with each other, neither having known before that they were both writing about it. It was a joke, they both said. His was such a man’s poem, and hers such a woman’s. The way I remember it, hers involved a mother holding a torn nightgown, his had footnotes referencing the Iliad. You get the idea, even if I’m remembering the details wrong. Anyways, as people know, I’m sort of blessed/cursed with remembering snippets of things like this from 20 years ago. I’m not sure there’s such a thing as “good memory”; I think if that space weren’t being taken up, I’d remember other things more thoroughly, and better. Anyways, I was blessed/cursed with this particular memory when I was listening, of all things, to a podcast from Slate of a discussion about Infinite Jest, featuring Katie Roiphe. (I’ve been writing about DFW; this was a “break.”) At one point Roiphe said something like, well, can we all just admit that a woman wouldn’t write a book like this. The other people on the podcast, both men, were a little sheepish and asked what she meant and she said, basically, well, you know, writing a big book to show that you could write a big book.

Well. I was wondering: is it ok for Hall & Kenyon to do some variation on the “men write like this . . . ” thing, but not Roiphe? If so, is it because they’re writers talking about their own work? Because they were jokey about it? Or just because they’re not Katie Roiphe, what with her whole history of using the “women do this” thing to make empirical claims about the world that have had a real, harmful effect?

Probably a little of all of these. And I think Francine Prose’s 1998 piece stands as just about the clearest reason of why you should probably stay away from such things all together.

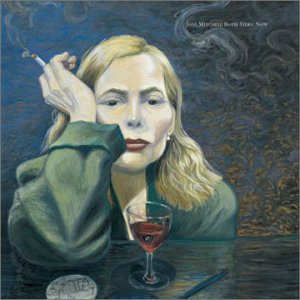

And then, just as I was thinking about all of this, I came across this article by Zadie Smith about Joni Mitchell. What an article! I’ve mentioned before the program I taught in when I was in grad school, how they wanted our students to write personal essays and tried to get them there by having them write this sequence of exercises with images, scenes, and reflections. It didn’t usually work, and the other departments really hated us, but I liked the effort to kill the five paragraph beast. Every now and then, I come across an essay, or a piece of a memoir, and I think, ah, that’s it: what we were trying to do. From Joni Mitchell to Kierkegaard and Tintern Abbey . . it shouldn’t work, and yet.

I was thinking was that all the things that made it such a great piece – how she’s talking about the necessary limitations on how much art we can love in one life, how she had gotten it wrong before, how she’s probably still getting so much wrong. Even after this revelation, she says, I’m still mostly talking about Blue: the album “any fool” owns. It doesn’t argue for why Mitchell is great; instead it helps you experience it anew through someone else’s ears.

And then it occurred to me that the piece was just about the exact opposite of one the New Yorker had recently run about the Grateful Dead, which was all about completists and the lost tapes and techno-fetishism – in other words, just about every stereotypical “male” way of looking at music sent up in High Fidelity. Prose brilliantly takes down the common tropes of those who think they favor “strong” “male” writing. But I have to admit, looking at these two pieces side by side, there’s something that makes me think women are more likely to achieve something I value in writing. Lots of men achieve it – but they tend to be men who have been ‘outsiders’ in some way, however you define that. But that’s so subjective! Well, yes. The acknowledgment of one’s own subjectivity – and limitations – is part of why Smith’s piece transports me in a way a “my band is the best!” piece never could. More writers of all genders should take it out for a spin.