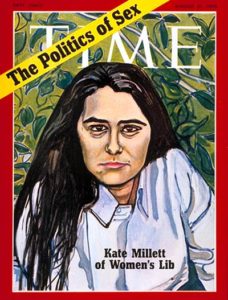

On August 31, 1970, Kate Millett appeared on the cover of Time magazine.

Probably this was the first, last, and only time the cover of Time has featured some one who became famous for a feminist PhD thesis turned book. The cover story was actually a group of articles – along with the central piece there was a profile of Millett’s life as an artist, and a pair of “pro/con” essays on feminism by Gloria Steinem and Lionel Tiger. The main article too, zig zags between pro- and anti-feminist statements, often quoting anonymous “average” people representing different viewpoints without much connective tissue. The mockery of feminism we’ve come to expect is there, but so is a sense that something big is happening and Time is struggling to keep up, trying to make sense of it all and walk a middle line when none may be available.

If the Time pieces tell us a lot about how the mainstream was struggling to respond to radical feminism, it couldn’t encompass much about the book itself, which, like Shulamith Firestone’s The Dialectic of Sex, and Celestine Ware’s Woman Power, both also appeared in 1970, mixed disciplines and tones for a mix of scholarship and polemic, marked above all by the scope of their ambition. Sexual Politics is structured in three main parts, with the first and last devoted to critiques of authors who were darlings of the counterculture for their sexual frankness, including D.H. Lawrence, Henry Miller, and, of course, Norman Mailer. These are the parts most people talk, but the middle section is the real heart of the argument, as she traces an overall pattern of liberation and backlash from the nineteenth century onward. It includes comprehensive readings of a range of Victorian authors from Ruskin to the Brontes. I’ve always known about the Nazi’s pro-natalist ideology but the first time I ever about the specific policies the Nazis implemented to turn back feminist progress, like instituting university quotas, was when I read Kate Millett.

Norman Mailer may have thought she was coming for his balls, and Irving Howe may have sneered at her “middle class mind,” but reading the book, you can’t help but feel that her real sin was actually taking what she’d been taught seriously, actually thinking that literature isn’t a parlor game but actually has something to say about the world.

Sadly, the mixed bag of the August 1970 coverage was better than what was to come. In December of the same year, they ran an article called “Women’s Lib: A Second Look,” which attacked Millett’s bisexuality as a way to attack the movement. Many of her later books deal with the personal fall out of her time in the spotlight and her struggles to continue to work as an artist. In 1998 she wrote an essay called “Out of the Loop and Out of Print” and she wondered in response to the latest “who killed feminism” tone, how an out of print author could do that.

Since then, there’s been more attention to the books and Sexual Politics in particular, with a new edition in 2000 and another one earlier this year along with some interesting pieces about Millett and her relevance.

But in an odd way, I think, the weird back and forth of the August Time piece, reflects something no retrospective can: the feeling of instability, that everything is up for grabs. To my mind what was present in 1970 and was lacking so long after (and perhaps seems to be coming back now) was not a reverential sense of the “power of literature” as many retrospectives focus on. It’s the intellectual ambition, idiosyncratic nature of books like Millett’s, Firestone’s and Ware’s, all of which blend disciplines and tones, mixing critique and utopian longing.

Norman Mailer certainly had some sense of that when he devoted a whole book, The Prisoner of Sex, to attacking Millett. The high-Mailerism is on display of course – he refers to himself in the 3rd person and comparing including statistics in writing to thinking about laundry lists while fucking. And yet, his actual response to Millett is not much different from the mainstream: he concedes pretty much the whole of the liberal demands for economic equality, but lamenting the more radical claims for “a cultural revolution and a sexual revolution.” If this is revolution, he notes, maybe he’s not a revolutionary after all.

“This world is white no longer, and it will never be white again,” James Baldwin, Mailer’s one-time friend with whom he argued with perhaps a little more respect but little more understanding, had written in 1955. In 1970, it seemed even to Mailer that the world was no longer male, and would never be male again.