Last night I ended up seeing Howl after messing up the times for the movie I actually wanted to see. It was one of those great unexpected viewing experiences. I’m sure a lot of people will hate it. There isn’t really a script: the whole thing is made up of scenes from Howl’s obscenity trial, Franco as Ginsberg talking to an unseen interviewer, and Franco reciting the text over a truly odd set of animations. It doesn’t come close to passing the Betchel test, but it’s hard to fault it for that when Kerouac, Ferlinghetti, Neal Cassidy and Peter Orlovsky get about three lines between them. There are also lots of great photos of the young Allen & friends, which are gorgeous and heartbreaking the way the photos of young Dylan in the Scorcese documentary were. When the real Ginsberg sings over the closing montage, you kind of start to weep a little. The closest thing to it I can think of was Chicago 8 from a few years ago. It’s hard to know what to say about the animations: Moloch is a giant calf like the golden calf you destroy in Sunday School pagents. There are lots of phallic fields and the approaches to animating lines about the cocksman and Adonis of Denver or sweetening the snatches of the sunrise are not metaphoric, to say the least. But the whole thing made me kind of weepy. I mean, first of all, putting basically the entire text in a movie is gutsy. Why not team up with Oprah and have a whole series of movies that are nothing but animated recitations of great books? Maybe that will be Franco’s next project, or his Columbia thesis, if he doesn’t first get inspired by this role to throw potato salad in the face of professors who lecture on Dadaism.

Last night I ended up seeing Howl after messing up the times for the movie I actually wanted to see. It was one of those great unexpected viewing experiences. I’m sure a lot of people will hate it. There isn’t really a script: the whole thing is made up of scenes from Howl’s obscenity trial, Franco as Ginsberg talking to an unseen interviewer, and Franco reciting the text over a truly odd set of animations. It doesn’t come close to passing the Betchel test, but it’s hard to fault it for that when Kerouac, Ferlinghetti, Neal Cassidy and Peter Orlovsky get about three lines between them. There are also lots of great photos of the young Allen & friends, which are gorgeous and heartbreaking the way the photos of young Dylan in the Scorcese documentary were. When the real Ginsberg sings over the closing montage, you kind of start to weep a little. The closest thing to it I can think of was Chicago 8 from a few years ago. It’s hard to know what to say about the animations: Moloch is a giant calf like the golden calf you destroy in Sunday School pagents. There are lots of phallic fields and the approaches to animating lines about the cocksman and Adonis of Denver or sweetening the snatches of the sunrise are not metaphoric, to say the least. But the whole thing made me kind of weepy. I mean, first of all, putting basically the entire text in a movie is gutsy. Why not team up with Oprah and have a whole series of movies that are nothing but animated recitations of great books? Maybe that will be Franco’s next project, or his Columbia thesis, if he doesn’t first get inspired by this role to throw potato salad in the face of professors who lecture on Dadaism.

From Uncategorized

Fragmentary Thoughts about Writing and Roland Barthes’ Mother

Men enter by force, drawn back like Jonahinto their fleshy mothers.

A woman is her mother. That's the main thing.

It’s probably not a coincidence that both these writers work in the seams of genres, from Benjamin’s not-quite-essays and epigraphs to Barthes’ mythologies and the pseudo-dictionary of “A Lover’s Discourse.” I remember one of my favorite grad school teachers saying that if we got nothing out of what we were doing, perhaps we would have a chance to give that book to to the right person.

Mothers, when they are guests at dinner, eat well, like children, but seem absent. It is often the case that they cannot follow what we are doing or saying. It is often the case, also, that they enter the conversation only when it turns on our youth; or they accommodate where accommodation is not wanted; smile and are misunderstood. And yet mothers are always seen, always talked to, even if only on holidays. They have suffered for our sakes, and most often in a place where we could not see them.

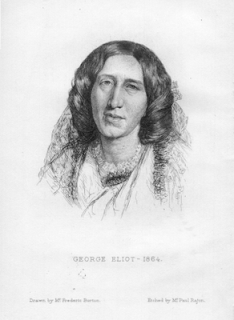

Six Thoughts on the final books of Middlemarch

Last weekend I had a lovely dinner with my Middlemarch reading mates. I sped through the final books to be prepared, jotting down notes as I went. At dinner, I launched into an impromptu speech on the comparative trends in the 19th century novel in England, France, and Russia. This isn’t really my field (I’ve never really had a clearly defined one – such is the beauty of the Comp. Lit major), but halfway through I thought, hey! I actually know something about this. This is the other side of the well-commented upon impostor syndrome common among academics: you worry for years that you’re a fraud but then, slowly you realize you actually know what you’re talking about, at least some of the time, which is an odd feeling.

Anyways. Six thoughts!

1) I loved reading Middlemarch but I can’t say the experience was completely immersive – probably I’d need to read in the period a little longer first. Throughout my reading life I’ve gone through phases where I find it very hard to concentrate on serious reading, and others where I can’t get enough of it. This is part of why I’m suspicious of the-internet-is-killing reading thing: in my experience web or channel surfing or what have you comes as a result of distraction, rather than being its cause. 19th century literature certainly does have a different pace – and of course reading it in one go is different than how the original readers would have encountered it in serialized form. But it does seem my reading improved over the course of the novel, as the writing started to feel more ‘modern’ to me – which is not inherently a good thing, of course, except insofar as it meant the writing was feeling less strange, with meant I was acclimating myself. I wish more writers wrote more honestly about their reading experiences – boredom, frustration and all – not the ‘oh I can’t concentrate anymore’ self-laceration, but the foibles of it.

3) What happens in novels? I remember, years ago, watching Dangerous Liaisons with a good college friend and her brother. The brother kept saying “why don’t the just drop the bomb!” He knew the characters were supposed to be doing cruel things, but it seemed silly to him that they did this through letters and mind games and not violence. And it’s true: if you’re used to contemporary movies, it feels weird, a world without violence where conflict must be found elsewhere, where the set pieces are constant: dinners, this or that person coming to call. And if you’re used to contemporary fiction, it’s the world without sex that strikes you: I mean, you understand about the Victorians at all, but how do you have knowledges about marriage without it?

4) People talk about Balzac as important in writing novels about money in a way that was previously frowned upon. Middlemarch is not really a novel about money but it is a novel about position and profession. Fred and Will need to find a position in order to win Mary and Dorothea and are held back by expectation and the meddling of their elders. Lydgate needs to be more successful to save his marriage. Causaban’s scholarly impotence mirrors the failure of his marriage. These men’s struggles for position in so many ways mirror the women’s struggle for satisfying marriage and each sheds light and sympathy on one another’s.

5) While Eliot takes on and in many ways achieves the challenge of giving a comprehensive portrait of her town, the working class characters and the servants are marginal and fall down. This is pretty universal in 19th century lit. of the canonical variety. I’ve thought a lot about why being an English major so often feels small ‘c’ conservative, despite the political affiliations of its practitioners. As a wee lit major taking women’s studies majors, you’re often immersed in something like Eliot or Austen or Wharton while your soc. major friends are reading about nannies. This tension probably led me to a lot of the ruminating on the topic of how gender and social class intersect, like I was trying to do here.

6) Surely when Woolf called this a novel for grownups she meant that we get at least three marriages at the start rather than seeing them at the end – though of course we also get Dorothea’s second and Mary/Fred’s first at the end. The postscript sums things up in a way that makes it sound like our narrator is talking about real people, whose lives can be summarized as by a biographer. Here we get and interesting caveat to our happy ending, a hint that, pace #2 above, it’s not only a contemporary reader who finds marriage as a reward for virtue a less than completely fulfilling end: “Many who knew her, thought it a pity that so substantive and rare a creature should have been absorbed into the life of another, and be only known in a certain circle as a wife and mother. But no one stated exactly what else that was in her power she ought rather to have done – not even Sir James Chettam, who went no further than the negative prescription that she ought not to have married Will Ladislaw.” I can’t think of another ending that makes this kind of gesture towards its own limitations, in a how many story lines we have way, not some meta-meta hemming.

So, obviously, I didn’t read and write about two books every week this summer. But aside from Middlemarch and the three other books I blogged about, I read a great book by Julia Serrano about sexism and transsexuality, one of Anne Lamott’s memoirs, and a book about teaching by a certain controversial radical Chicagoan, and I have a post coming up on Jean Baker’s great book about the suffragette’s. So, if you count Middlemarch as a couple books, it wasn’t too too shabby.

Is it OK to be foolish?, in which our narrator can’t refrain from television references: Middlemarch Chapters 34-42, Book 4, “Three Love Problems”

“For My Part I am Very Sorry for Him”: Special Pleading (Chapters 22-33)

(To the left: Victorian novel on the mantle of my bedroom in a Victorian mansion in S.F.).

Lydia Davis, “Varieties of Disturbance: Stories”

The first time I came across Lydia Davis’ work was in the Nerve “Naughty Bits” collection. It was a piece called “This Condition,” and it’s just about the sexiest thing you’ll ever read, though my tastes on the matter have been known to be atypical. Since then I read her collections Almost No Memory and Break it Down and now this most recent collection.

Dispatches from the Provinces: Middlemarch Chapters 11-21

I am currently sitting in the Isadora Duncan suite of a lovely B&B near the Haight Ashbury section of San Francisco. So, reading the Victorians in a Victorian! Quite lovely. Up until this morning, however, I was at my parent’s suburban home, where I read this second set of chapters where you start to pull back from Dorothea’s story and get a sense of the social landscape of Middlemarch. Now, being from the suburbs of a Midwestern city may not be the perfect socio-cultural analogy to the Midlands, but it got me thinking about the Provinces, following from Eliot’s subtitle “A Study of Provincial Life.” Of course the hero’s move from the Provinces to the city is an ur-subject of the bildungsroman and the 19th century novel – here we have characters with those ambitions who don’t move or who move and come back: Lygate had love in Paris but will have marriage perhaps in Middlemarch, Causaubon looks foolish to the younger would-be intellectual because he lacks German, and Dorothea honeymoon in Rome.

“Her ideal nature demanded an epic life”: 8 thoughts on the first ten chapters of Middlemarch

1) Once upon a time, when I was in high school, I had a certain teacher. In graduate school, the program I taught in had these peer mentoring groups, and the leader asked us to think about who our mentors were. I mentioned this certain teacher and there was an awkward moment: you weren’t supposed to mention a high school teacher as a mentor. But she was. In any case, the year I graduated, she bought a book for each person in our class that, she said, thought of in some way as a match for us. She got me Middlemarch, which was her favorite novel. I remember her saying something about plowing through it when she was pregnant and housebound, and maybe that was the way you needed to appreciate it. Now, I’ve gotten through quite a few Big Books in my day, but for whatever reason this one has been on the shelf – has moved many shelves – until now. When I took it down, I was shocked to find that my copy (now broken at the spine) has an inscription from her that mentions my reading it “when the spirit moves me,” so I hope she’ll understand.

“As Seen by Toads”: Week 2, #1: The New Yorker, 20 under 40 issue

So, apparently, according to a recent article in The Nation, Ambrose Bierce’s The Devil’s Dictionary gave this definition of realism: “The art of depicting nature as it is seen by toads.” Now, as it so happens, when I started playing around with fiction a few years back, it seemed to me that what I was interested in trying to do was, for a lack of a better term, psychological realism. I went to workshops where some people wrote about wise talking flounders (they were usually the guys) and the others (me and usually many of the women) wrote about a variety of topics that were nonetheless about homo sapiens in a world basically resembling ours, interacting with each other in ways that recall the way non-fictional people sometime interact with one another. Seeing as how the talking flounder camp liked to see themselves as heirs to every modernist, postmodernist, and magical realist they could name (and boy could they name them!) and tended to look at the actual world folks as backwards: too nineteenth century, too domestic, too female. Perhaps I was being sensitive. I developed this little rap about the 30s and realists being the real radicals and all that.

And here we aren’t, so quickly: I’m not twenty-six and you’re not sixty. I’m not forty-five or eighty-three, not being hoisted onto the shoulders of anybody wading into any sea. . . Everything else happened – why not the things that could have?

Two of the stories, by Joshua Ferris and Gary Shteyngart, try to take their punch up from reality through humor and satire, and really really didn’t work for me. Basically, their satire revolved around the fact that some people in Hollywood are assholes, except aspiring screenwriters who are nice but a little lazy (Ferris) and that the future will be bleak because no one will read books or really try to communicate except our nebbishy hero. Then there were the stories by Philipp Meyer and Rivka Galchen, which really didn’t seem to have any punch up at all: that is, they described things that happened to people. And as far as I could tell that was all they did, and it wasn’t enough, though of course I could be missing something. I feel this a lot with memoirs: it’s not that writing about yourself is self-induglent, just that when self-indulgent people do write about themselves they think what happened is interesting enough.

ETA: Hmm, the June 28th story is really good too: a writer uses a terrifying story she hears at a dinner party in her book and dreads running into the person who told it to her. That’s about it, but she gets at the strangeness of it, and by coming at it by this angle, with this remove, the original terrifying story holds us in a way it can’t when, as in the Meyer story, it’s just something that happens. The story is by Nicole Krauss. So, advantage Park Slope power couple.