Some thoughts and links on poetry, Palestine, and Kafka for the start of summer:

Poetry:

I recently was honored to give the keynote at LaGuardia’s Women’s Studies Conference on Adrienne Rich and in particular her time teaching in CUNY’s SEEK program. I’m hoping to publish a version of it somewhere soon, including a long section I didn’t get to include in the actual talk about her “Talking about Trees” response to Brecht. In the meantime, here are my two favorite pieces about Rich that have come out lately, in the many great ones that have come out since her death and the publication of her Collected Poems. First, here’s Michelle Dean in the New Republic, who makes use of the archives of Rich’s letters to her friend the poet Hayden Carruth to trace the many transformations of her mid-life: the end of her marriage, her husband’s suicide, and her coming out as a lesbian; her growing activism as a feminist and anti-war activist; her growing love of teaching (unlike many writers, she never resented the time spent with students and seemed to feel younger people had something to offer); the change in her poetry away from the formalism she’d been rewarded for early on; her increasingly difficult health struggles. I’ve been thinking a lot about this lately, about how dominant the awakening at middle-age narrative was in the stories of women’s lives I grew up with, and how much it applies to those of us today, many of whom grew up with feminism and who are having our children mid-life instead of coming out the other end of the early years of immeshment.

In Dissent, Lidija Haas covers a lot of the same ground, with an emphasis on Rich’s defense of poetry’s political engagement. When I was working on my talk, I was thinking a lot about how Rich approached teaching during the time of the Vietnam war and student strikes, how you do justice to the intensity of the moment while also seeing the classroom (and poetry) as something that should extend our thinking behind the heat of the moment. And then I realized some of Rich’s writings which are most intensely in the moment are from the ’80s, as the horror of backlash and Reaganism set in; Haas begins with Rich refusing an award from Bill Clinton calling art “incompatible with the cynical politics of this administration.” The answer for “why write poetry in ‘times like these” is that it is always times of these. I’ve also been thinking a lot about a passage in Rich’s 1981 essay “Towards a More Feminist Criticism” in which she expresses a different side of the issue: of course, activism and poetry mix, but about what is lost when writers are elevated to “spokespeople” above on-the ground activists and how we might look at the causal relationship between these things: “It’s not that I believe in a direct line of response, from a poem to an action: . . . In fact, it may be action that leads to poetry, the deed to the word.

Palestine:

We recently marked 50 years since the Occupation of the West Bank and Gaza. It has been a time of heightened activism both here and in Israel/Palestine, where political prisoners recently ended a forty day hunger strike and where hundreds of Jews from around the world recently joined Palestinians and for a series of non-violent actions connected to Israeli celebration of occupation. Two recent pieces point to how, in spite of everything, non-violent resistance still matters:

First, over at In these Times, a good piece by Tamara Nassar about the results of the recent Palestinian hunger strike. Prisoner solidarity is such an important part of the history of liberation struggles, and it’s easy to think there’s no leverage to be had over the brutal Israeli government, but Marwan Barghouthi is one of the most respected figures in the Palestinian community, and we’re in a period where international solidarity can’t be ignored.

And at Jewschool, Jodi Melamed has an interesting piece about the Sumud freedom camp, an inspiring action to help the families of Sumud return to their villages. Melamed talks about something I’ve wondered about a lot – Jews who want to oppose the occupation and Israeli violence but haven’t come around on BDS. A lot of times those of us who support BDS react with frustration to these folks – BDS, we point out, is the international, non-violent solidarity moment liberals claim they had wanted (if only there was non-violent resistance, we would support it!) But Melamed makes a convincing case that if there are actions like the Sumud one (inspired in part by Standing Rock), and organizations like the Jewish Center for non-Violence to organize and support them, people who aren’t there on BDS can take action, and when we come together on non-violent action, it dissipates so much of the rancor that marks the debate. It’s not about compromise or meeting in the middle, but a realization that, as I believe is very often true, action guides our beliefs, not the other way around.

Kafka:

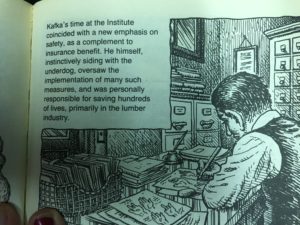

This semester in my fiction writing class I taught The Metamorphosis for the first time. I’d had it on there before, but always took it out in the end of semester crunch. To prepare for the discussion, I happened upon something a student gave me years ago: this little book, which, despite appearances, is not a kind of spiffed-up Cliff Notes but is a real book, and a fascinating one at that, co-written by R. Crumb and offering gorgeous visual riff’s on Kafka’s work plus their own take, one which emphasizes Kafka’s Jewishness and the role of the Prague ghetto in shaping his vision. There are lots of telling details I didn’t know, but this is the one I keep coming back to: this account of the details of Kafka’s famous “day job”:

Did everyone know this but me? I mentioned this to J., who said, I don’t know if you want to go there with the political implications of this: was worker protection the model for hated bureaucracy? But I think about it differently: I like the idea that this person who, at least in most versions of him we have, is so apart from others, from comfort, from his own body, that we think of him as barely functioning in the world, let along thinking he could shape it, let alone doing so – – – that this fragile man maybe did more good than all of us robust good citizens? To plagiarize Jamaica Kincaid writing about a different corner of the world and its cruelties, there’s a world of something in that, but I can’t get into it right now.