2018 was my first full year as a parent of two, my first full year without my mom. I went back to work, wrote a little but not that much and read more books than last year but not as many as I would have liked. Here’s my list and some thoughts.

The Best/Most Important Book I Read This Year

Kenanga Yamatta-Taylor From Black Lives Matter to Black Liberation. I read way too little serious non-fiction this year. Blame the baby or my grief or the relentless grind of the news, but it’s also that I’m still settling into the reading habits that fit an academic who doesn’t really do academic work anymore: sometimes I read things I think I might want to teach, or want to review, and there’s a proliferation of interesting new books coming from the Left that seem appealing to turn to. In any case, this book was as good as everyone said, and, unlike some Left books about contemporary topics I never felt it was mostly a compendium of things I’d learned from reading articles – she blends Civil rights history with reporting to historicize the movement. One of the key arguments that I think is so important is that, even though the backlash to Civil Rights was of course vicious and effective but that, specifically in terms of public opinion, there was a huge shift forward by the 70s in terms of recognition of racism and rejection of racist narratives to explain inequality. I feel like this is so important given the understandable pessimism people have about shifting public opinion. There’s also a lot of good stuff on the encapsulation of the African-American political class and the history of Black engagement in and around the left.

The Grief Syllabus:

I’ve been writing an essay on and off with this title since just a few months after my mother died, about what I read/was reading/wanted to read/felt I should be reading about grief. I avoided the Big Grief books for the most part, but the thing about death and mothers is that they find you.

Marge Piercy, Colors Pass Through Us. In that essay about grief and reading which perhaps I will finish sometime, I talk about trying and failing to find something to read for her service, and how my aunt suggested something by Marge Piercy. I thought about My Mother’s Body, which is the title poem of a beautiful book about mourning but it’s also about regret and unlived lives and felt altogether wrong and, as it were, too depressing for a funeral. But it was a good suggestion: in The Art of Blessing the Day she tries to write poems that would work for ceremonial occasions, something I’ve been thinking about a lot since she died and you want poems or words to mark things, not to stand around in some bar reading and have someone say “that was nice.” A little later I picked up this book, and there it was: a poem called “The Day My Mother Died.” It’s about longing and absence, and also too depressing for a service but to sit with it was just what I needed. I like the opening lines because they take me to a place I both want to and can’t bear to visit: the brief moment in which I knew and did not know, in which it now she seems she was both here and not here:

“I seldom have premonitions of death.

That day opened like any

ordinary can of tomatoes.

The alarm drilled into my ear.

The cats stirred and one leapt off.

The scent of coffee slipped into my head

like a lover into my arms and I sighed,

drew the curtains and examined

the face of the day.”

Sharon Olds, The Living and the Dead

Not about grief, exactly, but grief and motherhood is making me think a lot about the lifecycle and how we do and don’t mark or remember parts of it. I’ve long read Olds, of course, but I’m not sure if I’d read this book cover to cover before. I know it was very influential on people I know who wanted to be poets in the 80s and 90s, and would/should have been on me if I’d the guts to write poetry back then. Anyways, I was struck by the organization of these poems – from the dead to the living, from the fathers to the sons, especially the deep dive into family history that is the “The Guild.”

Sherman Alexie, You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me. I had wanted to read this book, Alexie’s memoir about his mother’s life and death and their relationship, before my mom died. After she died I put it off. Then Alexie’s #metoo moment happened, which I have really complicated thoughts about I might write about at some point, as Alexie is one of the few male artists caught up whose work seems painful to let go of. Then I decided I was ready and read half of it; then we went on a trip and it was too big to fit in the suitcase so I put the rest off. It was a complicated reading experience, is what I’m saying. The book itself is fascinating and uneven, written in over a hundred small sections, some no more than a page, which are reflections on their relationship, fragments of memory, and poetry. It’s a story about abuse and neglect and how the damaged damage each other, which is all related to the complicated feelings I have about his #metoo moment. But it’s a beautiful book, his books are beautiful in a particular way no one else’s that I know are, and it helped me grieve and I missed it on that trip, and there aren’t too many books I’d probably say that about.

Books by Friends:

Bianca Stone, Someone Else’s Wedding Vows. When me moved into our house last year, I decided books by friends was my favorite section to organize (and the only one I’ve managed to organize well). For the purposes of our book organization on the shelf, it includes mentors, colleagues and teachers, so I’m including this beautiful book by Stone, who I was lucky to study with at the Bowery Poetry Club. Stone does poetry comics; she makes videos I’ve shown in classes and at dinner parties; she’s light and weird and wild and funny.

Carley Moore, 16 Pills. This could also go in another category: books I wanted to/was supposed to review but didn’t get to, but “books by friends” is a nicer category, no? I taught with Carley way back when at NYU; we taught in a program that wanted to get students to write intricately woven essays; it seemed impossible to me then and now; a few years after I stopped teaching there, I wrote, for the first time, an essay that was something like the essays that program wanted students to write. I don’t write many of them, but Carley does.

Part of the reason I never wrote the review of this book I was supposed to is that it made me feel like I was inside it and instead of a review it would have ended up one of those essays I rarely write. There are a few reasons for this. She’s about my age and is writing about my world: writers, underemployed academics, parents in a no longer bohemian city. The more I read it, the more I also thought, it’s also a book about the internet, and not just the parts about internet dating: it gives the still-rare feeling of trying to write about what it feels to live this other life so many of us do now. She writes just casually enough that I felt like I’m reading blogposts that have been very well edited and woven (there’s that word from my essay-teaching days) together. It’s personal in a way that goes beyond what we mean when we say that writing about breastfeeding, sex, and hair lice is personal. It’s personal because it’s conversational, intimate, like a letter or a constructed journal or a poem. It’s personal because in the middle of an essay she talks about giving drafts of the essays she’s writing to friends and you imagine you’re one of them.

Alex Vitale, The End of Police. I’ve known Alex for a while now and I remember going to the book event for his first book and thinking it was too bad there wasn’t a bigger crowd for someone writing about such important work in an approachable way. In between that book and this one, Black Lives Matter happened, the left started to feel bigger, and the book event I went to for this book, one of many, was packed. It’s an encouraging thought about keeping at it. I felt the book was strategically written to appeal to a wide audience, going methodically through his important thesis about the overreach of police as the go to for every issue from drugs to homelessness to political dissent: an argument that may even appeal to police. Personally, I feel like owning the “anti-police” mantra for a variety of reasons, but I’m probably not the main target audience here.

Belatedly (books I should have read ten or twenty years ago)

Eileen Myles, Chelsea Girls; Michelle Tea; Valencia

When I reviewed Michelle Tea’s Black Wave a few years ago I mentioned James Baldwin’s bohemians in Another Country as a precursor. Somehow I had not yet read Chelsea Girls even though I love Myles’ poetry and essays. I’m not alone in my belatedness – Chelsea Girls (written in the 90s about the 70s) has found something of a second life after being a small cult hit – something not unlike Chris Kraus’ I Love Dick, which I also only read last year, and which, according to a New Yorker profile, sold only a couple hundred copies in its first decade, which reminds me of what people say about the Velvet Underground, that everyone who bought that first album started a band: everyone who bought one of those copies of I Love Dick got a PhD in cultural studies. Now I Love Dick is a TV show and a character based on Eileen Myles is on another TV show, one with its own #metoo problems, but that’s a story for another day.

I might have made the Myles connection to Black Wave if I had read Chelsea Girls then, though I think the Baldwin one holds up. In any case you can’t miss it with Valencia. The books are eerily similar and sure enough in the 2008 forward to the 2000 book, Tea says it was the inspiration. What’s interesting to me about this is how much early 70s New York and 90s San Francisco can both tell a story I don’t think can be told anymore.

J. and I were talking recently about how striking it is that the 90s are now as long ago as the 70s were from the 90s. Historically speaking it seems that a lot changed from the 70s to the 90s – less so now between then or now. But reading Valencia, I kept thinking how close it seemed to Myles and how far both seem from now. There’s the bars where everyone is you can just wander between, no one has a job, you can hustle – maybe people can live like that now but feels different.

The key thing in both these books is speed. You can’t hold on to one chapter, one relationship you are on to the next. Kerouac had the car but these books just move. They make you think that if you just live like this it is easy to write this way. Perhaps it’s true in the sense that if you live this fast and you find a little space where you are quiet enough or focused enough or on the right drugs (“I discovered coffee on Valencia” Tea writes, and makes it seem a miracle) but if you live that way, to find that is perhaps no small matter.

There’s also the swagger of these books, inevitably linked to their queerness. Late in Valencia, the narrator starts dating a sober woman. As she’s wondering how this will work, this woman talks about all the alcoholic men in her family. The narrator thinks, I have those too but I don’t want to talk about them. “These men,” she writes. She’s free of them and they just get a two-word sentence that’s barely a sentence. And then there are the short, beautiful, perfect chapters Myles and Tea both have memorializing someone who died young, the inevitably fallen soldiers of the battle to get free. Here it is, again, grief distilled:

Tea: “The workers at General don’t care about junkies, everybody knows that. Her poems were good, I thought. She was young and she’d get older and be different . . .she was on hold, someone I’d be friends with when she got her shit together. And then she died.”

Myles: “It was funny that he wasn’t drinking, but Paul was like that – he had a mind of his own. Nobody would even say out loud that he did it to himself. I felt that. He probably already had his life. There was no place for Paul to go. He had that great laugh.”

Patricia Hempl, I Could Tell You Stories.

I found this on my mother-in-law’s shelf this summer, and I’m including it in this category because it’s one of those books that’s somewhere between ten and 20 years old that has an uncanny valley feeling to it. It’s not that they are outdated, per say, it’s just that they aren’t ones that you are likely to hear people talking about; you vaguely heard about them way back when . . .but in another way this felt like the right year for me to read this book because along with grief and ritual writing I’ve been thinking a lot about personal writing, ho it justifies itself, and Hempl writes about that too, how she always ended up writing about the things she didn’t want to, like religion. There is also this sentence: “Refuse to write your life and you have no life” which she states not as her own belief but as a belief one clings to when one is writing, and which I feel more and more to be the case, now that I am older and crave solitude and reflection more than ever, and now that I am finding out what and why I sit and do this when accomplishment and career no longer mean much if anything.

Sandra Cisneros, The House on Mango Street.

This is more belated in the sense of “classic I’m embarrassed I’d never read up until now.” I’d read bits and pieces here and there and even used some as exercises in class, and the vignettes work very well for that. I picked it up at an air B and B we were staying at in Boston and as soon as I started it I knew I would end up teaching it, which I did this fall in my fiction writing class. What I especially loved is the intro to the anniversary edition I landed on, in which she talks about how they book came to be, looking back with affection and awe at the daring of the once-young self who scrambled together the pieces.

The Completist

Mary Gaitskill, Someone with a Little Hammer and The Mare.

J. bought me “Hammer,” Gaitskill’s first book of essays, last year and along with finishing The Mare, her most recent novel, she’s now one of the few authors I’ve read completely (the books at least; I’ll catch up on that New Yorker stack this year.) I loved both but it was Hammer that was the revelation: along with her brilliant take down of Gone Girl, there is a wondrous, long essay about animals, family, children, how we bring them in and what we owe them, themes and stories that are reworked in The Mare, which tells the story of a would-be artist and her relationship to kids she meets through the fresh air fund, and one of those kid’s relationship with a horse. I’ve written about Gaitskill a few times before, about why her treatment of cruelty is so rare and important; I once tried to write an academic paper about how she’s really a religious writer; that went nowhere obviously but I still believe it. Anyways, there’s a reason that she’s one of the view contemporary writers I’m a completist about, but if you have to start somewhere I’d suggest Someone or Don’t Cry.

Philip Roth, Exit Ghost and The Humbling

Back when I was trying to write a dissertation that included Roth, I had dreams about him. They were probably something like the dream Anya Ulinich describes in the brilliant Lena Finkel’s Magic Barrel: the horny old master asking who you were to be writing, and you weren’t that beautiful anyways, so. . . I didn’t write a lot this year, but one thing I really enjoyed writing was this obituary for Roth in Jacobin, and in preparation I read through these two late books, two of the only three of Roth’s thirty-some books I hadn’t yet read. (The last is his final, Nemesis, a sweeter and nostalgic which I read half of and then put aside perhaps out of a desire to have some unread work of Roth’s to return to. In the obituary I tried to think through what he had meant to me and others. What I came away with Roth embodies so much about the postwar liberal order that feels, for good and for ill, now to have definitively passed for good, and these beautiful, sad, elegiac books set me in the mood.

One of the stranger things that happened this year is that on the basis of this review a lovely bookstore owner invited me to be on a panel at the Brooklyn Book Festival with some fancy people including his biographer. It was a strange experience because I realized I was supposed to be the “critical” one, the feminist who would speak against him, which left his biographer, who I should say was wonderful, to talk about how wonderful he was, and how she didn’t understand how anyone could find his work sexist, and how universal it all was, and I muttered a stammering defensive response, even though the quote of mine had to do with his depictions of radicals and not feminism at all. Pretty soon they all went to sign their books and I had to shuffle aways since I don’t have any books. In any case, I wasn’t pleased with how I performed on the panel but I like the piece I wrote and I was glad I got to say goodbye in a way to him this year.

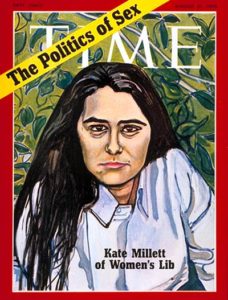

Books I Reviewed

Michelle Dean, Sharp. Only one this year, after many years where I did tons, partially because of the loss of my much beloved Open Letters Monthly where I started reviewing and where a lot of my stuff is still archived. I was excited about this collective biography, one of my favorite genres, excited about the women it was profiling, and excited about my first piece for In these Times, which was the first lefty rag I read way back when, in high school just a few years before, unbeknownst to me of course, my future partner was working as book editor. In retrospect, I was more disappointed in the book than my review let on – she had such a great topic and so much good material but, ironically given their “sharpness” doesn’t want to diminish any of her subjects by really critically engaging their visions. (Plus at least one really glaring and telling error we told the publisher about and as far as I know they didn’t respond to.) Looking at the review again, I notice this aside: “There is a fascinating companion book to be written about writers who navigated this while being “inside” the movement, writers like Adrienne Rich, Alix Kates Shulman and Kate Millett, all of whom appear in passing in Sharp as foils or critical targets.” Is anyone going to do this or will I have to try to?

Re-reads

Teju Cole, Open City

Another category that sometimes has a ton that had just one this year. I love a lot of Cole’s essays and he’s about the only person who I think has actually turned twitter into an art. And I really loved this novel when I first read it, the way it records a man’s thoughts about the violent history of New York as he walks around it, the way it feels different from what we’ve come to expect from NYC novels but also how it was the rare American novel that takes ideas seriously and presents a protagonist who engages them seriously, which is not to say that how he experiences them is separate from his psychology, just that they are not just a symptom of it, the way a lot of anti-intellectual fiction posits things. But it flopped when I tried to teach it, for reasons I’m still trying to figure out. I reread it this year for a seminar I was in, and a dear friend explained why she hated it in ways that I kind of loved and made me want to hear more about the novels especially you all have loved or hated recently. Unless you hated Ferrante, in which case you are just wrong.

Odds and Ends

Lenore Skinazi, Free Range Children.

If you’re a New York parent, you probably remember Skinazi’s famous article about letting her kid ride the subway by himself and the backlash she faced and her resulting theory about letting kids have more independence. I’m very sympathetic to the argument so somehow picked this up and it’s one of the very few parenting books I’ve read start to finish. It’s more a set of blogposts, than a book, though, and she has some annoying libertarian ticks the take away from the argument – independence for kids is a worthy goal and most things are overworried about and a few are not but not every rule is ridiculous and a few things we should actually worry about more!

Michael Wolff, Fire and Fury.

What can I say? I read an illegal pdf mostly while breastfeeding. Yes it was gossip, yes gossip is somewhat important, yes it was really this year, yes it’s all gotten worse since then.

Sharon Olds, Odes

I decided to pick up another, more recent book of Olds’ after reading The Living and the Dead. I wanted a book of odes because I use Alexie’s odes in my introduction to literature and creative writing classes and was possibly looking for a replacement on account of the whole problem I talked about above when I talked about Alexie. J. always says he likes every band’s first or second album best, and I always resist that because I like to believe we get better with age but I often agree – and this feels like a late middle career album – the themes and the craft are there, but rougher around the edges, a little less care, a little less spark.

Ann Tyler, Back When We Were Grownups.

I read this instead of Alexie on that trip where Alexie didn’t fit in my suitcase. It was my mother-in-law’s book and I’ve always been curious about Tyler because I like what people call “middlebrow” fiction in a lot of ways, and I like traditionally-plotted domestic novels. Or I thought I did. But after this, and another similar book I’m in the middle of now, I feel like as much as plotting there is a social conventionalism to much of this stuff that’s why it gets called middlebrow that might be unfair but also feels a little insufficient these days. You don’t have to be dying starving or desperate or wondering about the end of the world to write interestingly . . but maybe you do, just a little bit? So it seemed to me in 2019.

I was chatting online recently about whether it’s kids or the internet that are the reason I don’t read enough (spoiler: it’s the internet), and it occurred to me that some of the books I read to my six year old might count on a list now, which is a nice way to think about parenting and reading, but this is post, unlike my reading lists, is long enough already.

Here’s to more in 2019.